So your kid wrote something! Let’s call it a poem. And it’s creative and maybe funny, maybe it’s about unicorns being fantastic, and maybe they’re feeling pretty jazzed. But oh no, the spelling! And did they even capitalize anything? Have they heard of punctuation besides exclamation points? And from somewhere comes the thought, WHAT IS ALL THIS HIPPY-DIPPY POETRY @*#& AND HOW WILL IT POSSIBLY HELP MY CHILD BECOME A LITERATE EMPLOYABLE ADULT?

It’s cool. That’s what revision is for.

I believe it helps children tremendously to separate expression and mechanics when they’re writing. They should write a rough draft using their best guess spelling, getting all their ideas out, using their full thinking vocabularies. Then they revise.

I also believe that creative writing can be the core of elementary-level writing curriculum and can be used (in concert with other work on mechanics) to practice spelling, punctuation, grammar, and organization and all that important stuff. And I believe that approaching writing this way makes writing something a person could love doing in a way worksheets just never will.

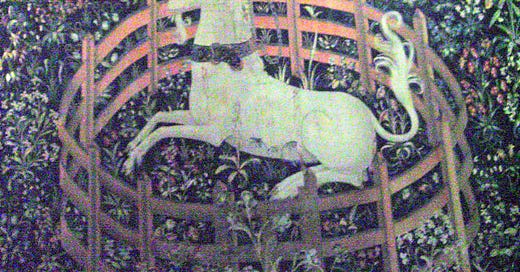

"The Unicorn Tapestries Room: The Unicorn in Captivity (detail)."

The Revision Process

Revision, as you probably have experienced in your own journey with writing, is most of the work for most writers, as they refine and reorganize their ideas. However children tend to be happy with their writing as is, so our revisions focus on mechanics. It’s only as they get old enough that spelling is less of a focus that I tend to ask them to reorganize and rethink the content of their writing. (Though I often push kids who whip off a half-assed two-liner to develop their ideas.)

I always praise children’s writing. Or more precisely, I respond to it with wonder and enthusiasm. I savor it. I read it aloud. I say wow and nice and mmm and I repeat pleasing and wild phrases. I tell them what their writing makes me imagine and wonder. I praise hard work. I appreciate humor and imagination. I praise moments of beauty and moments of truth. I read their work like it’s a pleasure and an honor, because it is.

I am never critical of children’s poems, even if I know they didn’t try very hard. If I want more from them, I find the seeds in what they’ve written and ask them developing questions. Say their poem was just I <3 cats LOL. (Real poem.) I might ask them to tell me some things they like about cats, or some other things they like. Or some other verbs they might apply to cats. I pet cats? I dream of cats? I eat cats? Encourage them to get a little crazy. If you do get into revising content, useful questions are: what is the poem trying to do? Is it working? It is never useful to ask if a poem is good. What does that mean, anyway?

When I help with revision, I’ll go through the piece with a pencil noting spelling, punctuation, legibility, and grammar issues, while the child looks over my shoulder. I often throw in a mini spelling or grammar lesson, especially if I see a couple of spelling mistakes that are similar. Sometimes in pieces without punctuation I ask them to put in the periods themselves, then I check over it with them — whatever feels like it will be good practice and successful for them.

I then ask the child to fix the issues we marked and show me the finished writing. Yay, completion!

How Can I Help When I’m a Bad Speller?

It can be intimidating to help kids with revisions when we don’t feel confident about our own writing skills. But the beauty is you don’t have to know everything. You just have to help them learn how to learn things. You know what? I’ve never been a great speller either. And that’s OK because then I can model looking words up. It becomes a problem we solve together. I got through grad school with just a hazy sense of when to use a comma (when there’s a pause!), but I learned more precise rules when I wanted to explain them to kids.

Start with what you do know. When questions come up that you can’t answer, model intellectual curiosity and look them up together.

Tackling Revision Resistance

Some kids respond to this revision process like they’ve been asked to crawl across the Sahara. I take the long view. I point out that they wrote something worth doing well – it’s going in their poem book! And I also make sure to give them a manageable amount of revisions, even if that means the final version is riddled with misspellings. A child who writes a page and then has to revise thirty spelling words will respond next time by writing three lines. Better not to penalize someone for writing their long and hard-to-spell thoughts. (When selecting a few spelling words out of many possibilities I go for two things: words that are so misspelled no one will remember what they say later, and words that are useful spelling words, perhaps several words that need similar changes, like adding silent e’s.)

It helps if the final product is something they can be proud of — a beautiful page with a picture, say, or part of a larger collection of work. Or maybe their revision is typed and sent out into cyberland somehow. Whatever makes putting in some effort feel worthwhile.

And it’s OK too to write things sometimes and not revise them. Life is long. Some days kids just need to write about yunakrnz in peace.

As someone who grew up with editors for parents and went on to persue a Linguistics/English degree, this is a great reminder, thank you! Also: yunakrnz!! :D