I recently read my students the lovely Brian Doyle essay “Pants: a note” (which you can find in his essay collection One Long River of Song — and do go find it, if you like funny, grateful writers who make you glad to be human), and this essay starts with a 379 word sentence in praise of favorite old pants, the kind held up with safety pins and that embarrass one’s children (ahem, Dad and your ancient paint-stained flannels, it’s a good thing I also like to wear favorite old clothes to death), and this essay got us into playing with very long sentences, the kind held together with lots of punctuation and conjunctions, which are, after all the safety pins of syntax. We played with long sentences. Then short ones. We started to feel around to see what the differences were, what their various delights could be.

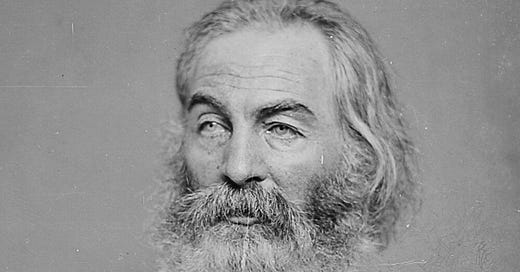

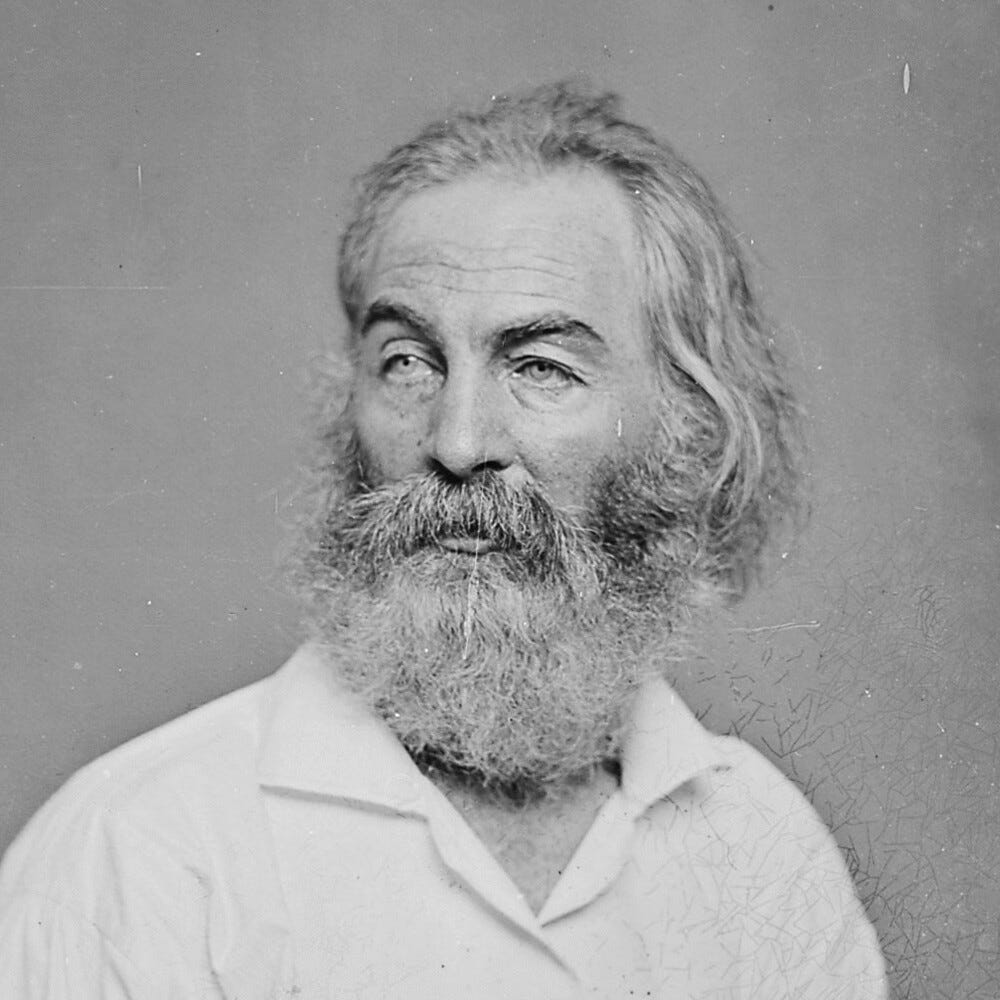

With my teens, I did this with an eye towards revising their work. We also took a detour to look at the poetry of Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson, the King of Expansiveness and the Queen of the Fragment respectively, because yes this same premise of long and short is at play in poetry, both in the sentences and fragments in poems, and in line breaks and stanza breaks.

We looked at a few lines of Whitman’s Song of Myself:

Have you reckon’d a thousand acres much? have you reckon’d the earth much?

Have you practis’d so long to learn to read?

Have you felt so proud to get at the meaning of poems?

Stop this day and night with me and you shall possess the origin of all poems,

You shall possess the good of the earth and sun, (there are millions of suns left,)

You shall no longer take things at second or third hand, nor look through the eyes of the dead, nor feed on the spectres in books,

You shall not look through my eyes either, nor take things from me,

You shall listen to all sides and filter them from your self.

And Emily Dickinson’s #479:

Because I could not stop for Death –

He kindly stopped for me –

The Carriage held but just Ourselves –

And Immortality.

We slowly drove – He knew no haste

And I had put away

My labor and my leisure too,

For His Civility –

We passed the School, where Children strove

At Recess – in the Ring –

We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain –

We passed the Setting Sun –

Or rather – He passed Us –

The Dews drew quivering and Chill –

For only Gossamer, my Gown –

My Tippet – only Tulle –

We paused before a House that seemed

A Swelling of the Ground –

The Roof was scarcely visible –

The Cornice – in the Ground –

Since then – 'tis Centuries – and yet

Feels shorter than the Day

I first surmised the Horses' Heads

Were toward Eternity –

Then we messed around with the line breaks. What happens if you break Whitman’s expansive, bombastic lines into short ones? What happens if you put Dickinson’s compressed precision into long lines?

Quickly we see things change:

Have you reckon’d

a thousand

acres much?

have you reckon’d

the earth

much?

Already there’s a different feel. My students felt there was a peacefulness and quiet that hadn’t been there before. I might name it as a hesitancy and sense of possibility, the kind that comes from pauses and unsaid things. (Which is, probably not at all coincidentally, such a beautiful element of Dickinson’s work.)

And there are more double meanings:

You shall no longer

take things

at second or third hand,

nor look

through the eyes of the dead,

nor feed on the spectres

in books,

Each line in a poem works as a unit, even as it might be part of a longer thought. So breaking Whitman’s lines up adds layers of pauses and half-finished moments that have their own meanings. “You shall no longer/take things” exists in this poem as well as the thought “You shall no longer take things at second or third hand.” “Nor feed on the spectres/in books” gives us a moment when those spectres are more real than they are once we know they are in the books, a moment that doesn’t exist without the line break.

My students, on the other hand, felt like putting Dickinson’s work into long lines destroyed something in her work, and I agree. And likewise, breaking Whitman’s lines up disrupts that expansive, uncontainable energy his poetry pulses with. These changes are real differences. Which means, cool, a tool we can play with!

How to get in on the fun:

You might look at the poems above, or others by these poets. Take the poems and try putting the first one into short lines and the second into long lines. How does that feel? Does it change the feeling or meaning of the poem? Does it still feel like a Whitman or Dickinson poem (or like the bit of one you started with)? What do long and short lines do?

Another thing, besides messing around with these poems, would be to revise something you wrote, thinking about these kinds of long and short options. What happens if you make the lines of a poem longer? Shorter? How about the stanzas? What happens when you punctuate your paragraphs with some short sentences or sentence fragments? Or if you use connecting words and punctuation to join ideas into one sentence? You can change anything you want as you revise, but do your revision with the lens of thinking about long and short (and medium) length chunks of words and thoughts. Sometimes all the words are fine, they just need a different form. Sometimes you can refine both.

Or to write a homage to something, like pants, that makes you want to go on and on — and see how long you can do so in one sentence.