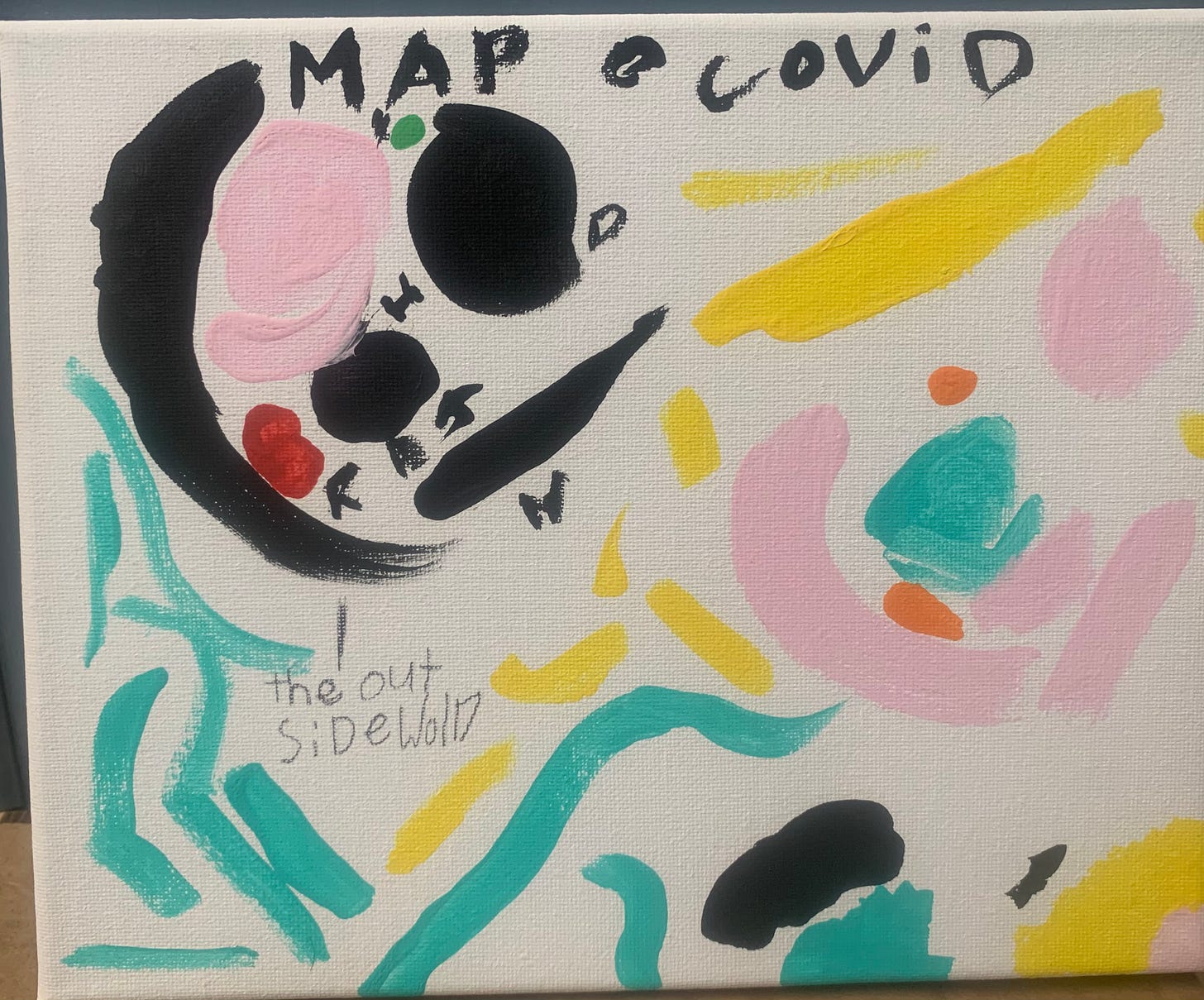

Before children write, they draw; art is their first storytelling medium and continues to be an important counterpoint to writing throughout elementary school if not longer. This is why map-making is such a potent form for kids. Maps mix drawing with narrative into something that is neither just a picture or just a description in words. Maps are a kind of visual storytelling, a visual transmission of meaning. They draw on visual and spatial intelligence as well as narrative skills and can often be a satisfying way to explain things that struggle to translate into words. I use maps in many ways in my class (more on that in the future) and recently we did a map-making project to explore how the pandemic has changed our lives.

Drawing life before the pandemic and life now

The prompt had three parts:

1. Draw a map of your life before the pandemic. You might include your home, classes, friends' houses, restaurants or stores, places you went on vacation or anything else that was part of your world. What colors show how your world felt?

2. Draw a map of your life now, during the pandemic. Does it look the same? Are there places you know in more detail now? Would you draw it to the same scale? How would you map virtual things? What colors is your world now?

3. Write a note explaining your maps and anything you notice about them.

The stories the maps tell:

My students’ maps showed many things. Several children’s Before maps showed a kind of satellite geography that included far away places connected with lines to their home, or even just floating in the corner, portraying a sense of travel and geographic business. Most of the Now maps had fewer locations on them. Some were pictures of computer screens. One student’s Before map showed detailed pictures of her school, the zoo, the ice cream store, and her grandmother (holding a glass of wine). Her Now map was a computer screen with all of those things on it, with big X’s through them. One computer key read “CAN’T” while another read “CAN.” If that doesn’t sum it up, I don’t know what does.

Rowan drew one map to show both times. Some of the black lines show places he no longer goes (the downtown strip of his town, the Mexican restaurant), while the blue lines show hikes he has started taking with his dad. He writes, “During covid I have had less school and more freedom at home but some places are still familiar like Ryker’s place, my house, the park. I have also noticed I have had more time to observe those places. My house feels a lot smaller and I know I should go outside more, but I feel sad and I want to stay in my room. I feel stuck to my house, that’s why I painted it a dark color.” He continued on to reflect on what he misses from before the pandemic, and also ways life wasn’t perfect then.

The maps were clearly a space children used to show the difficulties of being a child during the pandemic. However, not all the changes shown in the maps are completely negative. Several students drew new places their families have moved since the pandemic started. One family has spent months living with usually far-away grandparents. Another student’s Now map showed detailed walking routes all over his neighborhood, a kind of intimate knowledge of his home that was missing from the first map. And the adaptability and resilience of childhood — the ability to find magic and adventure — were evident in the maps too, as in Sinead’s map, which shows time instead of space. She drew how she passes through her day, with side paths and alternate routes to show the various things she does within a mostly static geographical space.

I came away from this project with two things affirmed: the importance of helping children have spaces and media to reflect on their experiences, and the sense that as adults we can use children’s reflections as maps to come closer to understanding their childhood, now — a geography like and unlike anywhere we’ve ever been.