A few years ago, as her audition to be my maternity sub, my dear friend Audrey Freudenberg turned my classroom into a Saxon mead-hall. The plastic folding tables went end-to-end, with me enthroned on a folding chair by the white board and the kids jostling elbows down the side. Imagine, she said, Becca is your king and your greatest dream is to win the honor of sitting beside her at the top of the hall. Tomorrow, she said, you will all go into battle to fight a fearsome foe. This may be your last night alive. So tonight you will eat, drink, be merry, and, she paused with all the drama of her deeply dramatic being, hear poetry. Each of you has a cup of mead in your hand. She held up her fist. Small fists appeared the length of the hall. At the end of each line you may pound your mead-cup on the table. They pounded. Are you ready? They were ready. And so she began to read Beowulf, in chilling and fluid Old English.

Hwæt. We Gardena in geardagum, BOOM went the mead-cup fists.

þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon, BOOM

hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon. BOOM

Call and response, action and reaction. One could almost smell the meat and wood smoke, feel the nudge of dogs sniffing around for bones between the folding chairs. Spoken aloud, cheered on by small warriors, the dry archaic words came alive. The kids ate it up. Even without food or drink, or the ability to understand what she was saying, they would have happily kept feasting for a long, long time. Sometimes all we need in life is the chance to bang an imaginary mead-cup.

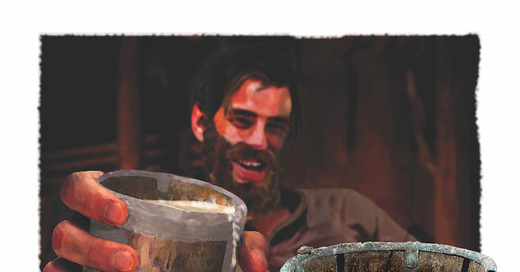

"Anglo-Saxon drinking vessel" by Wessex Archaeology

I myself cannot read Old English with either the fluency or panache that Audrey can, but I do like to write Old English riddles with the kids. At some point most years, we take a look back at the history of English, and I often tuck this prompt in then.

In Old English poetry, rhyming is not a thing, but meter and alliteration are crucial. In the most basic form, each line comes in two parts with a pause in the middle (for mead-cup thumping). Each line need three stresses, two before the break and one after. All the stressed syllables in a line should start with the same sound. This sounds complex, but when you say the poems out loud it quickly becomes clear, as in this riddle from the Red Book of Exeter, translated into modern English by Michael Alexander and E. S. Raymond, alliteration emphasis and mead-cups mine:

I am fire-fretted (BOOM) and I flirt with Wind; (BOOM)

my limbs are light-freighted (BOOM) I am lapped in flame. (BOOM)

I am storm-stacked (BOOM) and I strain to fly; (BOOM)

I'm a grove leaf-bearing (BOOM) and a glowing coal. (BOOM)

The last line is missing one of it’s alliterative g’s, which opens up a little space for the kids’ poems to be imperfect, a healthy example I think. Oh, and the answer? A beam of wood.

Old English poets also liked something called “kennings”: poetic phrases that fill in for a noun. Sea becomes whale-road, sun becomes world-candle, blood is battle-sweat, a ship a sea-steed. Thinking up your own can make for wonderfully playful (and yep, real nerdy) inside jokes.

Anglo-Saxon riddles can inspire a range of engagement: writing a poem in Anglo Saxon lines, writing a riddle, making up a kenning, doing all these things at once, just playing around with alliteration, or – who’s to say why not? – learning Old English and writing lines any ancient mead-cup slugger would thump for.